Euroscepticism

| European Union |

This article is part of the series: |

|

Policies and issues

|

|

Foreign relations

|

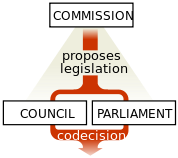

Euroscepticism is a general term used to describe criticism of the European Union (EU), and opposition to the process of European integration. Traditionally, the main source of euroscepticism has been the notion that integration weakens the nation state. Other views occasionally seen as eurosceptic include perceptions of the EU being undemocratic or too bureaucratic.[1][2] A Eurobarometer survey of EU citizens in 2009 showed that support for membership of the EU was lowest in Latvia, the United Kingdom, and Hungary.[3]:91-93

Contents |

Types of euroscepticism

There are two different strains of Eurosceptic thought, which differ by the extent to which adherents reject European integration and the reason for doing so. Aleks Szczerbiak and Paul Taggart described these as 'hard' and 'soft' euroscepticism.[4][5][6][7][8] Hard euroscepticism is the opposition to membership of, or the existence of, the European Union in its current form as a matter of principle.[7] The Europe of Freedom and Democracy group in the European Parliament, typified by such parties as the United Kingdom Independence Party, is hard eurosceptic. In existing western European EU member countries, hard euroscepticism is a hallmark of many anti-establishment parties.[9] Soft euroscepticism is support for the existence of, and membership of, a form of European Union, but opposition to particular EU policies, and opposition to a federal Europe.[10] The European Conservatives and Reformists group, typified by such parties as the British Conservative Party, is soft eurosceptic.

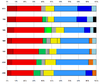

EU citizens attitudes towards the EU (Eurobarometer survey 2009)

A survey in 2009[update] showed that within the European Union overall, the majority of EU citizens support their country's membership: over 50% think their country's membership is "a good thing", and only 15 % think it is "a bad thing".[3]:91-93[11]:QA6a Attitudes vary greatly between countries. Support is greatest in Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain and Ireland, with about 70%–80% thinking that membership is a good thing.[3]:91-93 Scepticism is highest in Latvia, the United Kingdom, and Hungary, with only 25%–32% viewing membership as a good thing.[3]:91-93 In Britain, opinions are divided, fairly evenly, between those who think that membership is a good thing, a bad thing, or neither good nor bad.[3]:91-93

The majority of citizens (56%) believe that membership of the EU has benefited their country, though a significant minority (31%) believe that their country has not benefited.[3]:95-96[11]:QA7a Belief that the citizen's country has benefited from EU membership is lowest (below 50%) in the UK, Hungary, Latvia, Italy, Austria, Sweden and Bulgaria.[3]:95-96

About 48 percent of EU citizens tend to trust the European Parliament, and about 36 percent do not tend to trust it.[3]:110-112[11]:QA 13.1 Trust is highest in Slovakia, Belgium, Malta, Denmark, Estonia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Luxembourg; it is lowest in the UK (22%) and Latvia (40%).[3]:110-112 Trust in the European Commission and the ECB is slightly lower.[3]:114-117[11]: QA 13.2

A positive to neutral image of the EU dominates, with about 46% of citizens having a positive image and only 16% having a negative image; about 36% have a neutral image.[3]:130-133[11]: QA 10

History in the European Parliament

1999-2004

A study analyzed voting records of the Fifth European Parliament and ranked groups, concluding:[12] "Towards the top of the figure are the more pro-European parties (PES, EPP-ED, and ALDE), whereas towards the bottom of the figure are the more anti-European parties (EUL/NGL, G/EFA, UEN and EDD)".

2004-2009

In 2004, 37 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) from the UK, Poland, Denmark and Sweden founded a new European Parliament group called “Independence and Democracy” from the old Europe of Democracies and Diversities (EDD) group.

The main goals of the ID group were to reject the proposed Treaty establishing a constitution for Europe. Some delegations within the group, notably the United Kingdom Independence Party, also advocate the complete withdrawal of their country from the EU whilst others only wish to limit further European integration.

2009 elections

The elections in 2009 saw a significant drop in some areas in support for Eurosceptic parties, with all MEPs from Poland, Denmark and Sweden losing their seats. However, in the UK, the eurosceptic United Kingdom Independence Party achieved second place in the elections, finishing ahead of the governing Labour Party and the BNP won its first ever 2 MEPs. Although new members joined the ID group from Greece and the Netherlands, it was unclear as to whether the ID group would reform in the new parliament. The ID group did reform, as the Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) and is represented by 32 MEP's from 9 countries.

List of Eurosceptic parties

- Austria

Austrian People's Party, Alliance for the Future of Austria, Freedom Party of Austria

- Denmark

The Unity Party and Socialist People's Party (Greens) were against accession to the European Union, but only the Unity Party has withdrawal from the EU as a policy. The right wing Danish People's Party also advocate withdrawal.

- Estonia

The Independence Party and Centre Party were against accession to the EU, but only the Independence Party still wants Estonia to withdraw from the European Union.

- Sweden

The Left Party of Sweden was against accession to the European Union and still wants Sweden to leave the European Union.[13] The Swedish Democrats also favor withdrawal.

- Czech Republic

In January 2010, the Czech president Václav Klaus claimed that they "needn’t hurry to enter the Euro zone".

- United Kingdom

Euroscepticism in the United Kingdom (UK) is a very controversial issue and has been a significant element in British politics since the inception of the European Economic Community (EEC), the predecessor to the EU. In the UK, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) are the largest eurosceptic party, favouring repatriation of powers, and withdrawal. In recent elections The Conservative Party have campaigned against entry to the European Monetary Union and the Social chapter. The Labour Party membership is more eurosceptic than the party leadership, which is something the Conservative leadership has sought to exploit.[14]

The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) focuses on EU-withdrawal as its primary policy and receives significant support in European elections. It received 16.5% of the vote at the 2009 European Parliament elections, putting it in second place ahead of the then governing Labour Party. In the same elections, the far-right and anti-Europe British National Party was for the first time elected into the European Parliament. All Eurosceptic parties combined accounted for 28.2% of the vote in the 2009 European Parliament elections.

- Hungary

- Bulgaria

Ataka

- Greece

Popular Orthodox Rally

- Slovakia

Slovak National Party

See also

- Pro-Europeanism

- Europeanism

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnotes

- ↑ http://www.davekopel.org/Media/Mags/SilencingOppositionInTheEU.htm

- ↑ Hannan, Daniel (2007-11-14). "Why aren't we shocked by a corrupt EU?". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/3644012/Why-arent-we-shocked-by-a-corrupt-EU.html. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 "Standard Eurobarometer 71 (fieldwork June-July 2009)" (pdf). European Commission. 2009. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb71/eb71_std_part1.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ↑ Arato, Krisztina; Kaniok, Petr. Euroscepticism and European Integration. CPI/PSRC. p. 162. ISBN 9789537022204.

- ↑ Harmsen et al (2005), p. 18

- ↑ Gifford, Chris (2008). The Making of Eurosceptic Britain. Ashgate Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 9780754670742.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Szczerbiak et al (2008), p. 7

- ↑ Lewis, Paul G.; Webb, Paul D. (2003). Pan-European Perspectives on Party Politics. Brill. p. 211. ISBN 9789004130142.

- ↑ Harmsen et al. (2005), p. 31–2

- ↑ Szczerbiak et al (2008), p. 8

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 "Standard Eurobarometer 71 Table of Results, Standard Eurobarometer 71: Public Opinion in the European Union (fieldwork June - July 2009)" (pdf). European Commission. 2009. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb71/eb713_annexes.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ After Enlargement: "Voting Behaviour in the Sixth European Parliament" by Simon Hix and Abdul Noury

- ↑ Szczerbiak et al (2008), p. 183

- ↑ Jackie Gower and Ian Thomson, The European Union handbook, page 80